New Brunswick: Rutgers UP, 2010.

ISBN: 978-0-8135-4732-9

US$25.95(pb)

328pp

(Review copy supplied by Rutgers University Press)

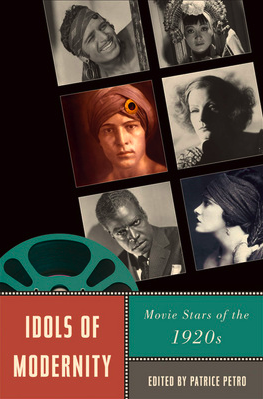

This excellent volume, part of the series Star Decades: American Culture/American Cinema, edited by Murray Pomerance and Adrienne L. McLean for Rutgers University Press (five volumes published, five more forthcoming, covering each decade of the 20th century in American cinema from the perspective of the star system) brings together a brace of incisive, elegantly crafted essays chronicling the major figures in the first years of the star system. Some of the choices are unsurprising even from a 21st century perspective; these are giants of their era in American film. Douglas Fairbanks, Buster Keaton, Rudolph Valentino, Gloria Swanson, Greta Garbo and Al Jolson all make requisite and much deserved appearances. Hovering on the outskirts of the cinematic firmament are names that might not mean as much to contemporary readers and/or viewers; Colleen Moore, Clara Bow, Anna May Wong, Emil Jannings, Ernest Morrison, Noble Johnson, Evelyn Preer, Lincoln “Stepin Fetchit” Perry and the formidable Marie Dressler.

Some were major stars during the 1920s, such as Clara Bow, the “It” girl, who personified sex appeal, but whose star faded rapidly with the advent of the talkies; while Anna May Wong (despite starring in the early two-strip Technicolor feature Toll of the Sea [USA 1922], never made it to the top solely because of racism, as was the case with Morrison, Johnson, and Preer. In contrast, the still-controversial Perry, whose utterly racist character Stepin’ Fetchit (which was also Perry’s screen name) thrived in 20s and 30s Hollywood, making him rich and famous. But Perry was also reviled by much of the African-American community, and while he achieved stardom of a sort, it was stardom of a peculiar and self-debasing kind, which has not aged gracefully, to say the least. Emil Jannings won as an Oscar for his performances in Josef von Sternberg’s The Last Command (USA 1928) and Victor Fleming’s The Way of All Flesh (USA 1928)—the only time in the history of the Oscars that an award was given out for multiple performances, rather than work in a single film—but soon decamped to Germany, where, sadly, he became one of the Third Reich’s most dependable box office draws.

One of the things that Idols of Modernity: Movie Stars of the 1920s makes abundantly clear is the essential ephemerality of stardom; how changes in public taste altered the fortunes of the stars, and how the coming of sound caused a complete revolution in audience tastes. Valentino, of course, died young, and so he was ensured a place in the same pantheon that would eventually embrace James Dean, Marilyn Monroe and even Heath Ledger; a brilliant career cut short by an untimely end. Garbo moved smoothly into the sound era with Clarence Brown’s Anna Christie (USA 1930), a vehicle tailored specifically to her Swedish accent, and then retired at the peak of her career to become a mysterious recluse.

Buster Keaton fell prey to alcoholism and his inability to cope with the rise of the studio system; an independent, Keaton functioned brilliantly on his own with such comic masterpieces as The Navigator (USA 1924; directors Donald Crisp and Keaton), The General (USA 1927; directors Clyde Bruckman and Keaton) and Steamboat Bill Jr. (USA 1928, director Charles Reisner). But when Keaton lost his studio due to a combination of changing audience tastes, financial reverses and personal problems, his star went into decline. Keaton was subsequently buried in a series of mediocre films at MGM with Jimmy Durante, which decisively ruined his career. Only much later, in the 1960s, would Keaton’s star rise again, thanks to the efforts of critics and preservationists.

Douglas Fairbanks Sr. built his reputation on his reputation on a devil-may-care attitude on screen and a series of films in which he performed a seemingly endless succession of spectacularly athletic stunts; he also was instrumental in the formation of United Artists in 1919, along with Mary Pickford, Charlie Chaplin and D.W. Griffith. Fairbanks’ stardom was cemented with his marriage to Pickford, “America’s Sweetheart,” a union that lasted from 1920 to 1933. Like Keaton, Fairbanks’ best films—Fred Niblo’s The Mark of Zorro (USA 1920), Allan Dwan’s Robin Hood (USA 1922), Raoul Walsh’s The Thief of Bagdad (USA 1924) –were made during the silent era, and his star dimmed with the coming of sound.

But Marie Dressler, whose career reached way back into the silents with Mack Sennett’s Tillie’s Punctured Romance (USA 1914), and who, because of her enormous physical bulk might have seemed a highly unlikely candidate for movie stardom, rocketed to fame in her last years with such films as George W. Hill’s maternal melodrama Min and Bill (USA 1930), for which she won the Academy Award for Best Actress, and George Cukor’s classic comedy Dinner at Eight (USA 1933); she died of cancer in 1934. And then, of course, we have the figure of Al Jolson, an energetic, egotistical, surprisingly charismatic figure who starred in Alan Crosland’s The Jazz Singer (USA 1927), a part talking film that took the nation, and the industry, by storm. Although it contained only a few dialogue sequences, and was for the most part, a silent film with music and effects, Jolson’s presence on the screen was electric, and he became a major star. So these are the major figures that Idols of Modernity: Movie Stars of the 1920s contends with.

And it does a magnificent job of it. Patrice Petro’s volume, with the able assistance of a stellar group of colleagues, effectively and resonantly fleshes out these figures for the contemporary reader, making them come alive again for a new audience of cineastes who might not be as familiar with them as one would expect. Petro’s introduction, “Stardom in the 1920s,” sketches a hectic, yet luxurious era in which visuals reigned supreme before the advent of sound, the slightest whim of major stars was obeyed without question, and millions of adoring fans around the world lined up at movie theaters to see the stars live out their dreams. Scott Curtis’s essay on Fairbanks Sr. is both sympathetic and erudite; Charles Wolfe is equally impressive on Buster Keaton’s long career, while Lea Jacobs offers a consideration of the Talmadge Sisters (Norma, Constance, and Natalie). Norma and Constance were major stars during the silent era, only to see their cinematic kingdom evaporate with the coming of sound; Natalie worked as an actor, but then married Buster Keaton in 1921, which worked out to no one’s advantage.

Mary Desjardins’ essay on Gloria Swanson, Colleen Moore and Clara Bow, entitled “An Appetite for Living,” aptly sums up the appeal and energy of these stars. All were major draws during the silent era, but only Swanson, through a combination of luck, shrewd self-promotion and an iconic role as aging silent screen siren Norma Desmond in Billy Wilder’s Sunset Boulevard (USA 1950) managed to keep her career and status within the industry relatively intact; indeed, she continued to work in films up to the mid 1970s, with a substantial cameo as herself in Jack Smight’s Airport 1975 (USA 1974). Lucy Fischer’s expressive and deftly researched essay on Great Garbo shows how much of her screen persona was the result of careful grooming on the part of director Mauritz Stiller, as well as the MGM publicity department, stressing her role as “the modern woman” in an Art Deco world.

Yiman Wang’s essay on the truncated career of Anna May Wong is both resonant and heartbreaking; a major talent, Wong was relegated, for the most part, to minor roles in major films solely because of her Chinese heritage. In the most heartbreaking setback of her career, she was denied the central role of O-Lan in the filmic adaptation of Pearl S. Buck’s novel The Good Earth (USA 1937; directors Sidney Franklin, Victor Fleming and Gustav Machatý); the role went to Luise Rainer, who won an Academy Award for the part. Perhaps one of Wong’s best-known roles is that of the sympathetic Hui Fei in Josef von Sternberg’s deliriously exotic Shanghai Express (USA 1932), but Wong also shines in E.A. Dupont’s Piccadilly (UK 1929) and William Nigh’s Lady from Chungking (USA 1942), a deftly made action film dealing with Chinese resistance against the Japanese during World War II.

Gerd Gemünden offers an equally penetrating examination of the career of Emil Jannings, who was a star in his native Germany, then in the United States, before returning home to Germany after winning his Academy Award. Krin Gabbard’s essay on Al Jolson, “The Man Who Changed the Movies Forever,” gives the reader a real insight into Jolson’s imperious, often tempestuous career in the cinema, while Paula J. Massood’s essay on the marginalized African-American stars Ernest Morrison, Noble Johnson, Evelyn Preer and Lincoln Perry does much to restore their work, in a new and perceptive context, to the public eye. Joanna Rapf’s essay on Marie Dressler, whom she accurately describes as “The Thief of Talkies,” based on her ability to steal scenes from even such accomplished and unforgiving actors as Wallace Beery, is at once affectionate and scrupulously detailed.

In a final, intriguing essay, Patrice Petro offers a consideration of the relationship between Marlene Dietrich, Anna May Wong and Leni Riefenstahl, and of two iconic 1928 still photographs of the three women together, taken by Alfred Eisenstaedt. Petro prints two versions of the photo, with subtle differences; in the first one, Dietrich is smoking a pipe, and Wong, in the middle of the photo, has her arms around Dietrich and Riefenstahl; in the second, more widely circulated photo, Dietrich’s pipe is absent, and Wong holds her hands in front of her, in a much more demure fashion. Petro’s elegant essay is a great way to close this groundbreaking book, with a consideration of the power of the image and what it conveys, or might convey; the potential for fluid sexuality, and the end of an era in which actors could move freely from one country to another, in favor of an era of fervent nationalism, which would lead, in the 1930s, to the outbreak of World War II.

All in all, Idols of Modernity: Movie Stars of the 1920s is a rigorous, insightful, and refreshing look at the stars of the 1920s, the world in which they lived, the directors, producers and studios who shaped their public image (often with the actors’ willing participation), and the audiences who flocked to see their films. The 1920s saw the consolidation of the star system, both in Hollywood and abroad; the zenith of silent, purely visual filmmaking on an international scale; and then, at its end, the greatest financial collapse the world has yet seen (we hope), and the coming of sound, which radically transformed the industry, and the art of filmmaking, for those who worked within it both in front of, and behind, the camera. In short, Idols of Modernity: Movie Stars of the 1920s is a superb, balanced, and deeply trenchant book that resonates in the mind long after each essay has been read; indeed, it is a book that the reader will return to again and again, finding new insights with each successive reading.